Morality is a difficult idea to process. One can think of the recent U.S. capture of Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela as an example. One can believe that the U.S. shouldn’t be involved in the politics of other countries for moral reasons. One can believe that an outside agent removing an autocrat who has crashed a country’s economy is good for moral reasons. I have friends who have escaped from Venezuela. It is clear that the Hugo Chavez and subsequently Maduro regimes destroyed the country’s economy and threatened their relatives. It sounds like the removal of Maduro was a good thing. Yet, I personally am troubled about U.S. involvement in other countries.

Moral decisions are difficult.

Recently, a well-known Evangelical writer confessed to having an 8-year affair with another woman while he was married. He has been married to his wife for many, many years. The writer (and a nationally-known speaker, by the way) subsequently has decided to quit his public life and to retreat into a private life to deal with his marriage difficulties. This change is probably the right thing to do. I am not going to mention this person’s name. You can find it easily on the internet.

I have heard this person speak live at an event that I attended many years ago. I found him moving, especially since he was a big proponent of the reconciliation of religion and science. He walked right past me on the way to the speaker stage. I never knew the person, but this recent tragic news made me reflect on my “interaction” with him.

Here is the rub to the whole story. This person has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (let’s abbreviate it as “PD”).

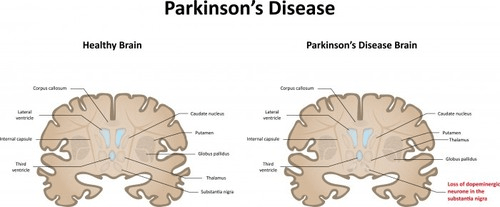

PD is a neurodegenerative disease of the brain that is universally fatal. It is more common in men and typically presents with symptoms at around 60 years of age. For unclear reasons, dopamine-producing neurons begin to die off in the part of the brain known as the substantia nigra pars compacta. Most people are familiar with PD due to its progressive and debilitating muscle movements. Helpful links are here and here. Treatment consists of using the medicine, levodopa, which replaced dopamine. Other treatments also are available. Regardless, this disease is progressive and fatal.

Image from Practo

Not every patient with PD has the initial muscle movement changes. Some patients can present with emotional dysregulation and psychiatric disease. In fact, I know of someone who mainly presented with memory loss before an official diagnosis of PD was made. In other words, PD is in on the spectrum of dementia disorders.

Here is a great open access article about PD.

The psychiatric diseases associated with PD can be vast, including, “…depression, anxiety, hallucination, delusion, apathy and anhedonia, impulsive and compulsive behaviors, and cognitive dysfunction…” See this open access link for information. It also is important to consider that disinhibition and hypersexuality are much more common in men with PD.

Back to the person described above, what if, what if, what if, this person had neurological changes leading to personality changes leading to bad decisions. This particular person is 76 years old, so if the affair that he was having occurred 8 years ago, then he was 68 years old when it started –prime time for neurological manifestations of PD to kick in.

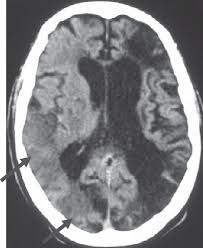

I have had personal experience with the personality changes associated with the various types of dementia. My father was a well known academic in the field of military history and had a long career. He developed dementia that was likely due to chronic infarctions (strokes) of the brain associated with advancing age. My father was a very decent person who tended to be on the side of kindness when it came to strangers. As his dementia progressed, he became an extremely angry person. He was angry in the ICU until he went unconscious and died. Honestly, I didn’t even recognize my father at that point — even though I loved him.

Brain of a patient with multi-infarct dementia (from International Psychogeriatrics)

My blog posts tend to be theological in nature. So, what does my writing above imply?

First, I think that the very essence of human nature or human personality is influenced by our biochemistry. Our essence is affected by time as our bodies become older, worn out, and scarred. Perhaps we live in a world of soft determinism. As animals, we have some degrees of freedom, but nature put limits on such freedom. Sponges rarely move. Pacific salmon have a semelparous life cycle that seems rather tragic. Humans can have a huge spectrum of emotions and behavior that lead to beautiful science, art, writing, engineering, and music.

Sponges (from One Ocean Foundation)

However, in the presence of time, the human brain typically atrophies or scars as we each get older. We don’t want to lose our good personality traits as we age, but many of us probably will.

This limitation of degrees of freedom will affect how we think about God, or conversely, no God. Our past experiences (including the physiology of the brain and diseases of the brain) can lead to changes or perhaps even lack of changes in how we think about God. I would imagine these changes could be problematic especially if one becomes anxious or angry in the setting of dementia.

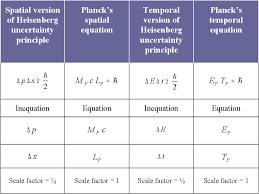

Second, I believe that God allows nature to have complete freedom in how nature operates. God may “lure” for creativity / novelty / love at all levels of nature, but nature can “choose’ to do whatever. The Second Law of Thermodynamics could be a theological example if we consider that the increasing loss of useful energy over time occurs because the universe works just that way — even if God perhaps desires the universe locally to be a perpetual motion machine.

Thus, God may lure us to not make bad decisions, but God also gives nature the freedom to have our hormones work in certain ways, our genes to be expressed or mutated in certain ways, and our brains to change in certain ways that risks detrimental behavior at times.

There is some degree of inescapability here. After all, we all die. Perhaps this aspect is a good thing. God is not interfering directly with our lives. Philip Clayton has coined the term “Not Even Once.” in terms of God participating in the world…not even once. God cannot interact with the world outside of known physical laws.

Image from Semantic Scholar

Perhaps God has interfered once (the Christ event, the accumulation of the Quran, the rare appearance of the Buddha, etc.) based on various religious traditions. Such ideas are singular divine events. However, if God interferes once, humans will risk believing that God will interfere again and again and again. Perhaps the human tragedy is that we think God will keep interfering with our lives to make our lives better or worse.

Regardless of the potential of a singular God event(s), I think it is important to consider that nature progresses on with limits such as gravity, the human spectrum of vision, DNA mutation rates, the expansion of the universe, and other factors. God may lure for us to be better humans, but our efforts to be good to the “other” may necessarily be limited by limitation of natural laws or the limits of our neurological personalities.

What does this all mean? Well, to go back to the original example of the fallen religious leader, he did some bad things in his marriage, but perhaps, he was neurologically impaired in such a way that the risk of bad behavior increased. I think we need to consider such possibilities among people in our lives, especially the elderly.

By the way, I am not a complete cynic here. I think God lures in real time and eternally. There is always the real chance for the good. Such a real chance can include your making a real and positive difference in the generations to come and can include the possibility of God’s immense of love of all creation, including God loving us even in specific ways after we die. At this juncture, I am ever the optimist.

Image generated by Google Gemini